Editor’s Note: This is a later nineteenth century account of memories stretching back into the mid-early part of the same century.

I was once paying a visit to one of my elderly parishioners who was not exactly ‘bed-fast,’ for she could get up from time to time, but being far past ‘doing her own tonns’ (turns), or little odds and ends of household work, was still house-fast, or unable to leave the house, even for the sake of a gossip at the next door. I found her, with her husband — a man who died a couple of years since at the age of ninety-seven — just sitting down to tea. As a rule, I carefully avoided meal-times in all my visiting from house to house; but on the occasion I refer to there was some deviation from the customary hour for the meal just mentioned, and the old couple were going to tea at the timely hour of about half-past two in the afternoon.

On finding them so engaged, I was going to retire and call in again later, or perhaps some other day. However, this did not suit the old lady’s views at all, and I had to sit down and wait until their tea was satisfactorily disposed of. Naturally we fell into talk, and as the old woman had lived in the district all her life, and most of it in the near vicinity, I began to ask her questions about local matters. Within a quarter of a mile from the house we were sitting in — one of a group of three or four — was a place commonly known by the name ‘Fairy Cross Plains.’ I asked her, Could she tell me why the said place was so called? ‘Oh yes,’ she replied; ‘just a little in front of where the public-house at the Plains now stood, in the old days before the roads were made as they were now, two ways or roads used to cross, and that gave the ‘cross’ part of the name. And as to the rest of it, or the name ‘Fairy,’ everybody knew that years and years ago the fairies had ‘a desper’t haunt o’ thae hill-ends just ahint the Public’.

I certainly had heard as much over and over again, and so could not profess myself to be such a nobody as to be ignorant of the circumstance. Among others, a man with whom I was brought into perpetual contact, from the relative positions we occupied in the parish — he was, and is, parish clerk — had told me that his childhood had been spent in the immediate vicinity of ‘the Plains,’ and that the fairy-rings just above the inn in question were the largest and the most regular and distinct he had ever seen anywhere. He and the other children of the hamlet used constantly to amuse themselves by running round and round in these rings; but they had always been religiously careful never to run quite nine times round any one of them.

‘Why not?’ I asked.

‘Why, sir, you see that if we had run the full number of nine times, that would have given the fairies power over us, and they would have come and taken us away for good, to go and live where they lived.’

‘But,’ said I, ‘you do not believe that, surely, Peter.’

‘Why, yes, we did then, sir,’ he answered, ‘for the mothers used to threaten us, if we wer’n’t good, that they would turn us to the door (out of doors) at night, and then the fairies would get us.’

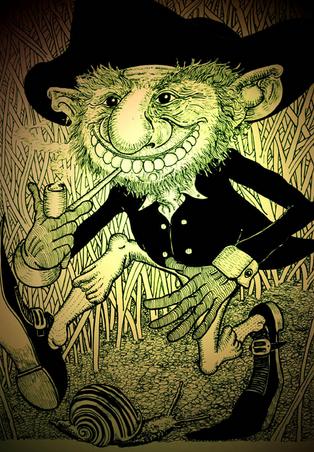

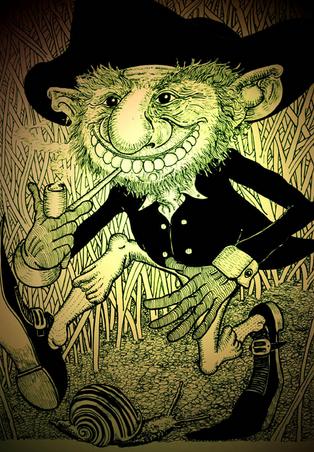

But to return to the old woman with whom I was conversing. I admitted that I had both heard of and seen the fairy-rings in question ; but what about the fairies themselves? Had anybody ever seen them? ‘Ay, many a tahm and offens,’ said she; ‘they used to come down the hill by this deear (door), and gaed in at yon brig-steean,’ indicating a large culvert which conveyed the water of a small beck underneath the road about a stone’s throw from the cottage. A further question elicited the reply that it was a little green man, with a queer sort of a cap on him, that had been seen in the act of disappearing in this culvert. Just here the old woman’s husband broke in with the query, ‘Wheea, where do they live, then?’

’Why, under t’ grund, to be seear (sure).’

‘Neea, neea,’ says the old man; ‘how can they live under t’ grund?’ The prompt rejoinder was, ‘Why, t’ moudi warps (moles) dis, an’ wheea not t’ fairies?’ This shut him up, and he collapsed forthwith. His wife, however, was now in the full flow of communicativeness, and to my question. Had she ever herself seen a fairy? the unhesitating reply was, ‘Neea, but Ah’ve heared ’em oftens.’ I thought I was on the verge of a tradition similar to that of the Claymore Well, at no great distance from Kettleness, where, as ‘everybody used to ken,’ the fairies in days of yore were wont to wash their clothes and to bleach and brat them, and on their washing nights the strokes of the ‘battledoor’ — that is, the old-fashioned implement for smoothing newly-washed linen, which has been superseded by the mangle — were heard as far as Runswick. But it was not so. What my interlocutor had heard were the sounds indicative of the act of butter-making ; sounds familiar enough to those acquainted with the old forms of making up the butter in a good-sized Dales dairy. These sounds, she said, she had very often heard when she lived servant at such and such a farm. Moreover, although she had never set eyes on the butter-makers themselves, she had frequently seen the produce of their labour, that is to say, the ‘fairy -butterì; and she proceeded to give me the most precise details as to its appearance, and the place where she found it. There was a certain gate, on which she had good reason to be sure, on one occasion, there was none overnight; but she had heard the fairies at their work ‘as plain as plain, and in the morning the butter was clamed (smeared) all over main part o’ t’ gate.’