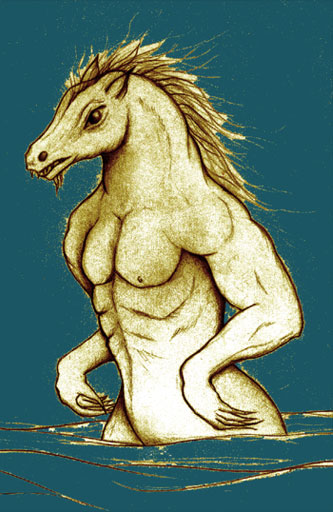

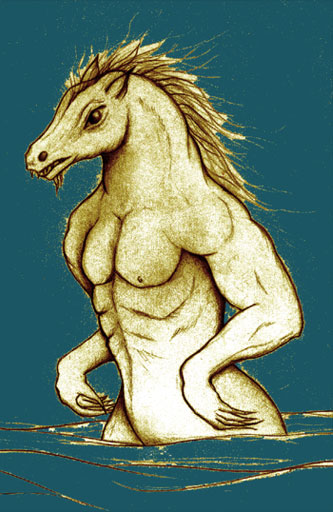

This is how the last each-uisge that was in Lewis came to his end: A man lived in Erista, in the parish of Uig, who was the tenant tacksman not only of that and the neighbouring village but of the extensive tract of land between Loch Roag and Loch Langabhat. In the summer season he used to send his cattle to graze on the moor with two females to look after them. The women lived in a shieling in Glen Langabhat-where the ruins of the shieling are still to be seen. The women were frequently visited by the each-uisge in human form, but as he conducted himself in no way disagreeably they did not feel any repugnance to his visits. In the course of time, however, he seems to have undergone a change of disposition, inasmuch as his conduct towards them became highly offensive. He not only insulted and ill-treated themselves, but committed great depredations among their master’s cattle-killing some of them on the spot and carrying some of them away. But, says my informant, he always had the form of a quadruped when he killed them on the spot, but of a man when taking them away and visiting the women. His indignities towards the women and his depredations amongst the cattle increased to such an extent that the women left the field to himself, and made their way to Erista, where they told their master how matters stood. Their master, not believing their reports, and deriding their cowardice, sent two ‘ sgallag’s’ to the moors to see what was the real state of matters. When the ‘ sgallag’s’ came in sight of Glen Shanndaig they saw the each-uisge in the act of taking one of the cattle away. This satisfied them, and they returned and told their master what they had seen. The owner of the cattle saw that he must get the each-uisge killed or else his cattle would be all lost to him. There was a man in Eashadir on the shores of Loch Roag who was a famous archer and who had killed some time before two each-uisge’s, one in Skye and another in the parish of Lochs (Lewis). To him, then, the owner of the cattle went and offered him a great reward if he could kill the each-uisge. The archer, whose name was Macleod, agreed to go at once. He accordingly took his bow and arrows and started for the glen, accompanied by his son, who did not know where they were bound for till they were half-way on their journey. When the son heard the object of the journey he would not by any means go, but wished to return home and let his father go alone. The father would not permit this, but bound his son with cords and left him there. Macleod proceeded alone on his way, and when he came in sight of the glen he saw the each-uisge coming up from the loch and making for him. He held himself in readiness, and when the beast was within range he let fly the arrow, which stuck in the creature’s side, but did not in the least impede his progress. As he came still nearer, the man let go a second arrow, which caused the each-uisge to stagger, but still he came on with his mouth wide open and his eyes glaring. The man saw he was in danger and took out the Baobhag, the Fury of the Quiver, and placing it waited till the creature was near, when he fired it so that it went in at its mouth and through its heart. The beast fell dead, and Macleod cut off its tail as a pledge that he had killed the each-uisge, and picking up the Baobbag returned to the tacksman, who rewarded him generously. Anon ‘Fairy Tales’, The Celtic Review 5 (1908), 155-171 at 166-168