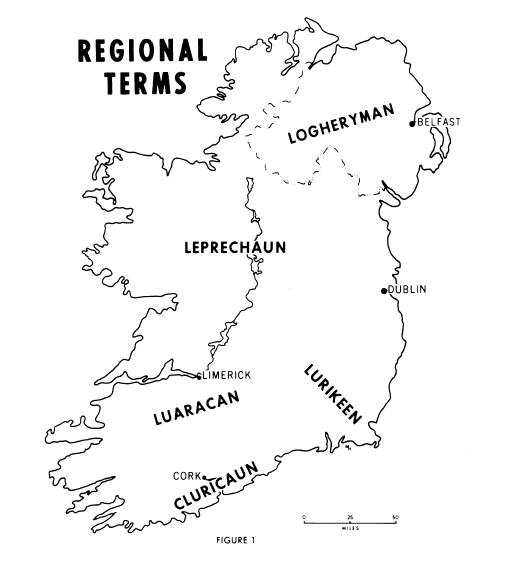

The Banshee (sometimes called an bhean chaointe – the mourning woman – in Munster) is a solitary supernatural being that warns Gaelic families of approaching deaths in their ranks. The Banshee is always a woman, though descriptions of age and appeareance differ radically. She is heard (and sometimes) seen prior to the death of a family member and ‘follows’ or ‘cries’ only families of ‘pure Milesian descent’ (i.e. pure Gaelic). Her typical approach to death is to scream three times in the night before a family member dies: confusion with seals, foxes, cats and cat-owls have all been reported! The scream is variously described, but is often shrill and deafening. In some cases, not all family members can hear the scream. Local tradition has sometimes made her into a ghost and she is sometimes cast as a surviving pagan goddess. But her name suggests that she is in that very large and loose category of ‘fairies’: the shee is the same as the sidhe, the Irish fairy folk.

Home region: The Banshee is found in Ireland above all, but there are similar traditions from Gaelic Scotland. There are also some intriguing legends from abroad, where Irish families have settled in other countries. The strong connection between family and banshee apparently means that the banshee will follow emigrees.

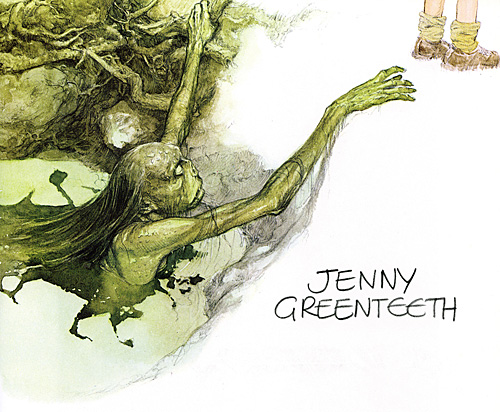

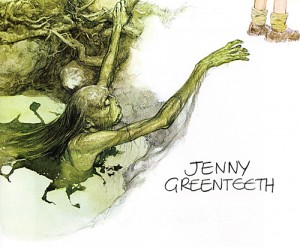

Physical Description: Sometimes the banshee is described as something resembling a ghost, sometimes an old barefoot woman and, in some descriptions, she is a beautiful radiant young woman. Her hair is uncovered and she often combs her hair: this may mark confusion with a keening woman who tears her hair? Her femininity comes through again and again, there is no male banshee, though see Marvel’s intervention below.

Earliest Attestation and etymology: The word banshee comes from the Gaelic ban sí (an bean sí, in modern orthography), literally ‘fairy woman’. The word first appears in English – at least according to the sometimes fallible Oxford English Dictionary in 1771. However, it appeared in Gaelic a century earlier, in a poem by Fiaras Feiritéir, and its use over the whole of Ireland, with few regional variants, suggests that it may be far older.

Banshee Locations: The Banshee is associated with the place of death, be that hospital or home, but she never seems to appear indoors. The banshee is seen or howls outside.

Banshee Sightings: A Banshee in Canada; Back from a Visit and the Banshee (Co. Clare); Banshee at the Window; Cats or Banshees; Convinced by the Banshee (Co. Offaly); Last of the Banshees, 1905? (Co. Clare); Lizzie Crow’s Banshee (Co. Cavan); Hampshire Banshee in Ireland; Mary Ann and the Banshee (Co. Sligo); Seals, Foxes and Banshees (Co. Donegal) (note that typically we should talk of a Banshee Hearing rather than a Banshee Sighting).

Banshee Story: The Banshee’s Comb and the Farmer’s Tongs

Banshee sayings: ‘The Banshee follows our families’, ‘The Banshee cries our family’.

Popular Culture: The Banshee has perhaps surprisingly not made it big in Hollywood or in modern bookstores. Patricia Lysaght wrote a very capable study of the Banshee, first published in 1986 (The Banshee), which was then re-released in a special shortened form as A Pocket Book of the Banshee in 1998, but neither book has become popular outside folklore circles. There was a 2011 film entitled Scream of the Banshee that involves a museum, an archaeologist and a box: the banshee screams her victims to death, which is not quite what tradition tells us, but at least gets into the spirit of things. A 1970 Hammer Horror Film Cry of the Banshee had absolutely nothing to do with Ireland or the Banshee save that one of the witches was called Oona (!). There is also, from Marvel Comics, The Banshee an Irish mutant man (!) who has a sonic scream.