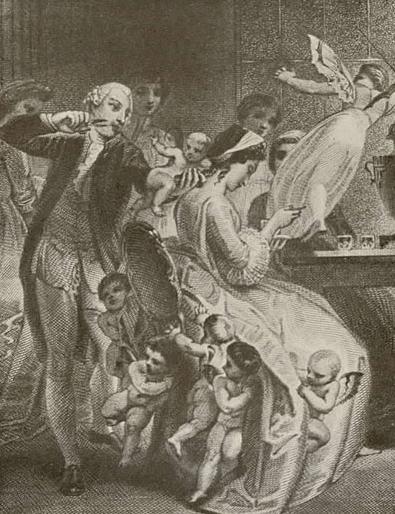

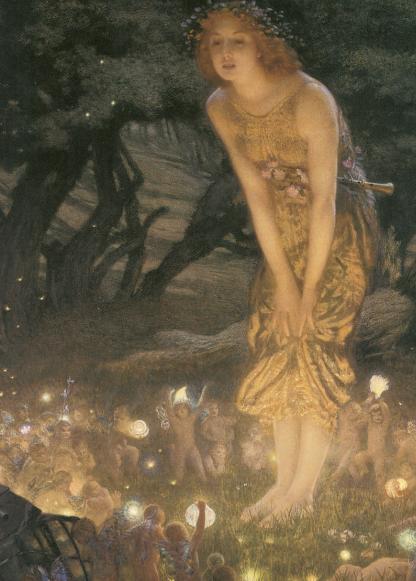

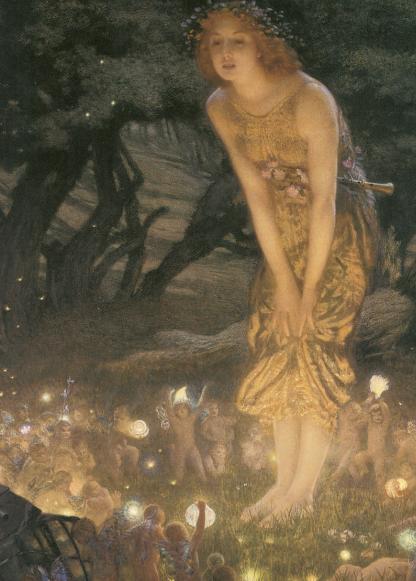

‘Fairy spirituality’ would have been a very strange concept to the rural Scots, the Welsh and Irish men and women who believed in fairies in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Their main concern was placating the fairies and, in a very few cases, of using fairies to work good or evil in the world. However, modern perceptions of fairies began to change with spiritualism in the second half of the nineteenth century. Spiritualism was all about sitting around a table and contacting the dead and by the 1890s it was a major social movement, often referred to as the ‘New Age’ of its day. Early spiritualist writers tried to explain fairies believing that fairies were, in fact, elemental spirits, the power behind the workings of nature. In doing this they were aping various ancient and, above all, Renaissance philosophers who had come to similar conclusions.

Fairies were never that important for spiritualists. However, a branch of spiritualism, theosophy, under the leadership of the legendary and rather frightening Madame Blavatsky (pictured), was inclined to look upon fairies as a vital part of any understanding of the natural world. In fact, read theosophy books or articles and you will constantly trip over fairy references. Today, we forget just how influential theosophy was in forming modern views of fairies. For example, Evans-Wentz had clear theosophist sympathies (as did several of his informants) in his Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (1911). Likewise the Cottingley Photographs, the most famous fairy photographs (and fakes) ever taken first came to light at a theosophist meeting. The Fairy Investigation Society founded in the 1926 had a clear theosophist agenda. Theosophy codified fairies and also explained exactly how they helped natural processes along and these ideas, for good and for bad, have affected how we depict fairies. For example Disney’s Tinkerbell cartoons have theosophist philosophy in several scenes: though their makers will have been completely unaware of this.

For anyone interested in reading vivid theosophists accounts three authors stand out. First, there is Geoffrey Hodson who published several books including fairy sightings, but most interesting Fairies at Work and Play, witha visit to Cottingley in 1922. Second, there is Daphne Charters’ fairy visions, that have now been edited into a beautiful volume by R.J.Stewart books: we include her channeled account of a fairy party elsewhere on this site. Then, finally, there is Dora van Gelder whose The Real World of Fairies includes perhaps the most coherent account of theosophy and fairies: for a description of a standard New England fairy and for an insight into how theosophists thought of fairies follow this link. Theosophy may not be taken seriously by many people today but writers like Charters, Hodson and van Gelder were the closest we have to a continuing fairy tradition through the middle decades of the twentieth century. Were they really any different from the tradition-bearers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? Yes and no.

Fairies had had a certain mystical cachet in the late 1800s and the early 1900s: the poet W.B.Yeats, for example, could boast of his fairy belief at swish London parties. However, by the time of the Cottingley fairies fairies were already becoming less fashionable. By the 1950s and the UFO craze interest in fairies dropped to historically low levels. The Fairy Investigation Society, for example, found that ‘although reports of unidentified flying objects received tolerant public notice, reports of fairy sightings encouraged press ridicule’ (Shepard 321). However, interest began to grow again in the 1960s and 1970s when two new trends helped to bring fairy belief back from the brink. First, there was increased interest in regional British and Irish traditions and, in other countries, in ‘native’ traditions. Then, second, there was what might be very broadly called ‘the hippy’ movement. ‘Hippies’ with their interest in ecological and spiritual matters found the theosophical vision of fairies to be attractive: though most of those who became fairy believers had no idea that they were adopting theosophist ideas; indeed, most would have had no idea what theosophy was.

In modern times fairy spirituality has broken down into five distinct if overlapping traditions: we’ve capitalised for the sake of clarity! First, there is Faery Magic; second Faery Wicca, third, Celtic Faery Shamanism; fourth, the Feri Tradition; and fifth the Fairyfolk. For those outside the magic fairy circle the differences between these five tendencies can be utterly bewildering and the profusion of ‘faeries’ and related words is a strange occult version of numerous socialist and communist sects on the fringe of the student movements in the late 1960s. But as these differences matter to practioners they should matter to anyone interested in fairy lore and fairy traditions generally.

Let’s start with Faery Magic, note the use of ‘faery’ as opposed to ‘fairy’ that has, since the early twentieth century, been used to signal a ‘knowing attitude’, let’s say, to fairies. Faery Magic is perhaps the lightest of the five forms here. Faery Magic involves a personal relation with faeries to achieve changes in the world: in terms of psychology, health and well being. Many faery magicians make the point that the existence of faeries is besides the point: the non-believer is interacting and (hopefully) individuating features of his or her own personality by communicating with ‘faeries’.

Faery Wicca refers to a branch of the Wicca religion. Wicca is, of course, a modern form of paganism that claims to have its roots in the rural traditions of Britain and Ireland: though many contest the supposed historical basis of this tradition, not least some of the most interesting Wiccans. Faery Wicca was pioneered, above all, by Kisma Stepanich, in the mid 1990s, a Wicca writer who was interested particularly in Irish traditions about fairies and who believed that these traditions could be recovered and formed into a spiritual discipline. It is very difficult to generalize but Faery Wiccans emphasise not only relations with fairies of various types, but also a more visceral attitude to nature and a greater attention to the passing of the seasons than mainstream Wiccans.

Celtic Faery Shamanism takes a shamanic approcah using the fairies as ‘familiars’ on the road to spiritual development. And the fairies, sorry faeries? ’Faeries are beings which occupy another world or dimension that lies close to our own… These are often called the Shining Ones or the Shining People. They are able to interact with humankind and contact between the faeries and humans was quite common before the advent of Christianity in the Celtic countries… The Faeries still exist in the bright realms that lie all around ours. Celtic Shamans are able to enter those realms and interact with the Shining Ones.’ Emma Wilby’s work on early modern witchcraft may suggest that Celtic faery shamans are attempting to revivify a long dead but historically attested tradition.

The Feri Tradition was associated above all with two mystics: Cora and Victor Anderson. Of this list of modern fairy tradtions it is certainly the ‘wildest’ including sexual mysticism and ecstatic religious ceremonies. Fairy lore is important but not central with tantric, huna and even voodoo rites and wisdom being mixed in! The Andersons have now both died: Cora passed in 2008. And the Feri tradition is reforming around new personalities and there has been a reversion to ‘faery’ among some practitioners, so watch out for even greater confusion in the future!

The Fairyfolk are a small, largely Irish tradition detailed by Dennis Gaffin in his Running with the Fairies. DG includes long passages where the Fairyfolk talk about their beliefs. A central idea is that the Fairyfolk are themselves fairies who have been born back into human form. The fairyfolk claim to be best in tune with their fairy brethren in the wilds away from cities and urban centres.